Like every year in the heart of autumn, winter weather enthusiasts start to become interested in the trends for the coming winter and whether it could be cold or mild. What will happen during the winter of 2025-2026? This is an early look using current trends…

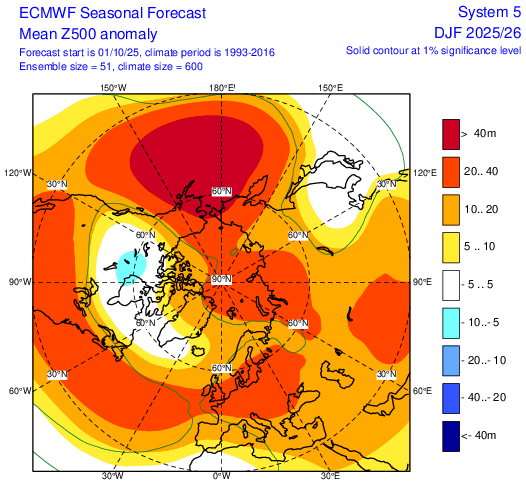

The ECMWF seasonal October update for 500 hPa heights indicates a +NAO (positive North Atlantic Oscillation) for December - February, but with a signal for higher pressure than average across the UK and Ireland. This does not mean there won’t be spells of low pressure dominating, but rather greater incidences of high pressure relative to the 24-year climatological mean. As would be expected with this +NAO signal, 2m temperatures are forecast to be above average in the +0.5C - +1C range.

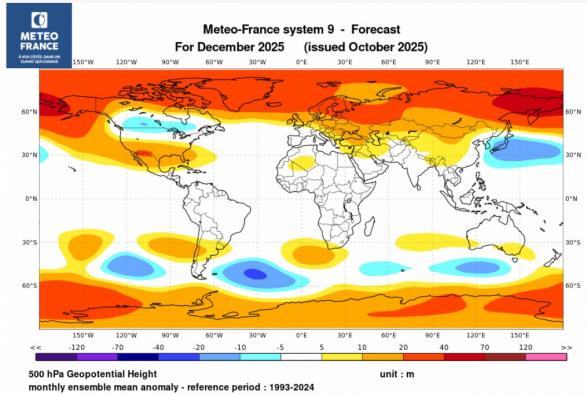

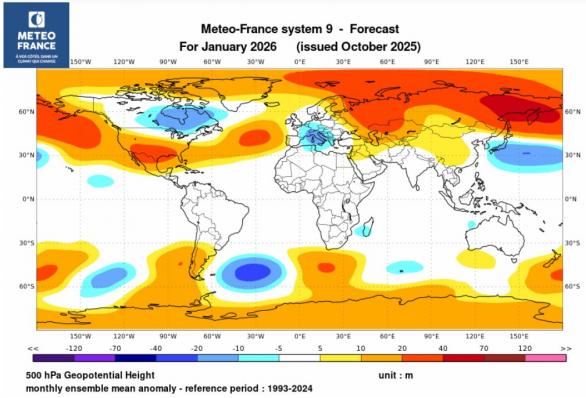

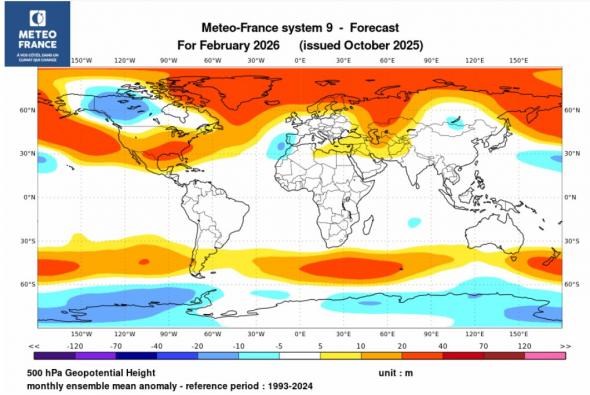

In contrast, the Meteo France seasonal October update for 500 hPa heights suggests a weaker tropospheric polar vortex with higher heights in the polar regions and lower over southern Europe than the 1993-2024 period, more particularly noticeable in January and February. This would suggest a greater chance of periods with a -NAO (negative North Atlantic Oscillation) - with no signal for above or below average temperatures over all 3 months, which suggests potential for cold spells coinciding with the -NAO periods.

Other seasonal models have yet to update for October - i.e. UK Met Office, NCEP, etc.

As well as weather model predictions there is a range of indices at our disposal, but in this blog I will deal with some of the most important of them which have the most impact on Europe indirectly (ENSO, QBO, solar) or directly (Atlantic SSTs). The coupling between these is also essential to know the weather regimes that are likely to occur.

There are two main categories of indices for the seasonal trend:

In the case of this outlook, we will only look at the seasonal indices this far out at over a month away from winter starting.

ENSO (El Nino Southern Oscillation)

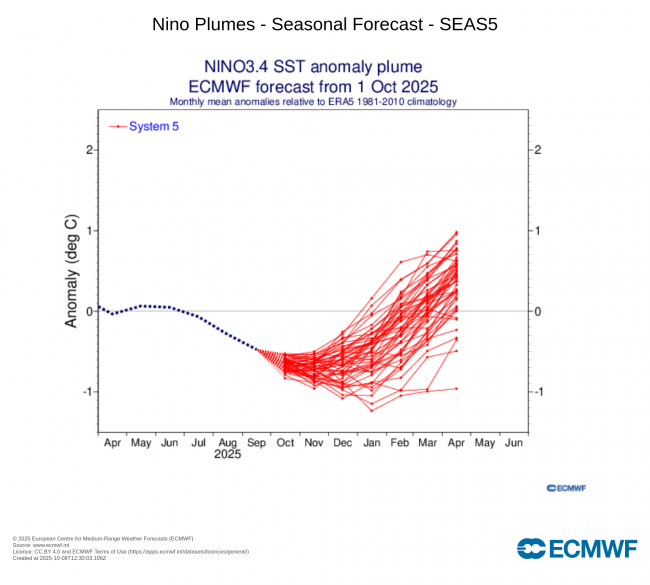

The recent update from the U.S. NOAA Climate Prediction Center ENSO recent evolution, current status and predictions page on 6th October states a La Nina Watch is in force.

ENSO-neutral is present.*

Equatorial sea surface temperatures (SSTs) are near-to-below average across

most of the Pacific Ocean.

A transition from ENSO-neutral to La Niña is likely in the next couple of months,

with a 71% chance of La Niña during October - December 2025. Thereafter, La

Niña is favored but chances decrease to 54% in December 2025 - February

2026.*

So, we can deduce that La Nina is likely to develop in late autumn and perhaps continuing through winter 2025-26.

La Nina can bring two types of winters to Europe: either mild and wet, or cold and dry. But these different types are dependent on where the coldest SST anomalies of La Nina are situated over the tropical Pacific along with the status of other major winter pattern drivers of QBO (Quasi-Biennial Oscillation) and position in the solar cycle.

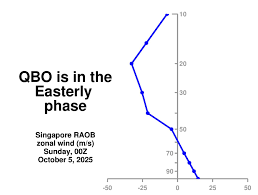

For example, the combination of La Nina and an easterly QBO statistically favours a greater chance of a major sudden stratospheric warming and an increased chance of cold weather than La Nina and a westerly QBO.

Quasi-Biennial Oscillation

The QBO is a regular variation of the winds that blow high above the equator. Strong winds in the stratosphere travel in a belt around the planet, and every 14 months or so, these winds completely change direction. It can affect the Atlantic jet stream. The speed of the winds in the jet stream weaken and strengthen with the direction of the QBO. When the QBO is easterly, the chance of a weak jet stream, sudden stratospheric warming events and colder winters in Northern Europe is increased. When westerly, the chance of a strong jet, a mild winter, winter storms and heavy rainfall increases. The QBO this winter is forecast to be easterly, so a greater chance of the Polar vortex (PV) being weaker than normal. Currently, the polar vortex is already weaker than average. A weaker PV is also more susceptible to Sudden Stratospheric Warmings displacing or splitting the vortex, leading to a greater chance of colder weather for northern Europe.

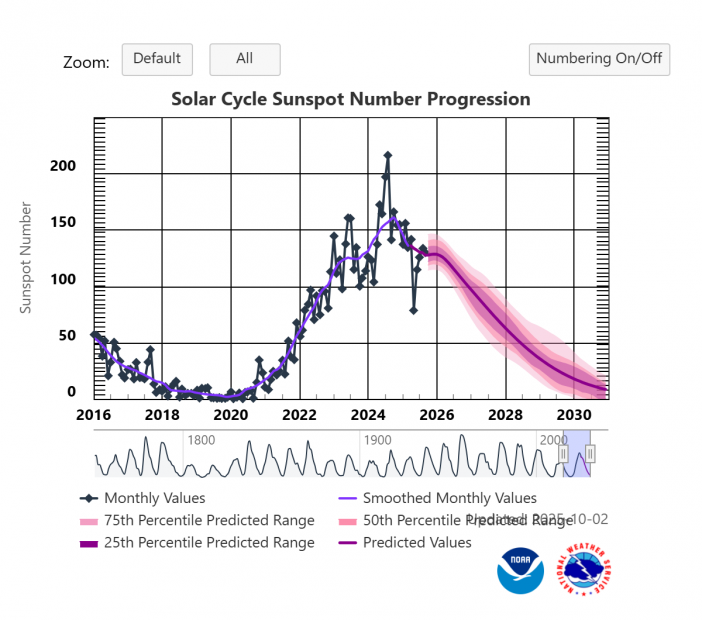

Solar cycle

Although the link is not robust, winters during solar minimum have an increased chance of being colder than average than those winters in the solar maximum, though there is normally a lag of a year after minimum and maximum when the increased chance or cold/milder winters is likely. We have now passed the peak of the solar maximum of solar cycle 25 and solar activity is now in slow descendancy towards the solar minimum expected sometime in a year or two after 2030. But we are still in the solar maximum and sunspot activity will remain fairly high through the winter, higher solar activity tends to be correlated with a colder stratosphere and stronger polar vortex winter.

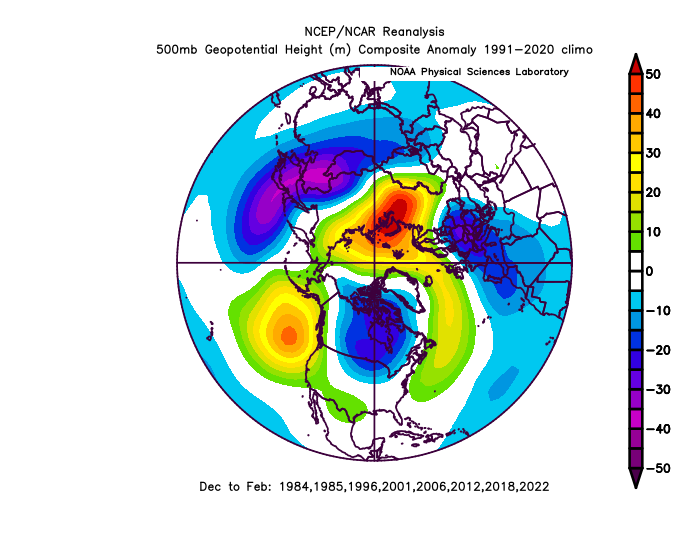

Analogue winters with a weak or moderate La Nina and eQBO

Below is a composite chart of 500 hPa heights for the 3 winter month period December - February when there was a weak or moderate La Nina and easterly QBO, winters used are from 1980s onwards, as this is when QBO data is available from.

As you can see, higher heights feature over higher latitudes of the far north and northwest Atlantic and NE Europe and lower heights over mainland Europe. This suggests a higher chance of a negative NAO (North Atlantic Oscillation), which could bring colder spells with wintry risks to the UK.

The elephant in the room - climate change

There’s no escaping the fact the world continues to warm at unprecedented levels, global temperatures in 2025 have remained at near-record levels, with 2025 projected to be one of the top three warmest years on record. January 2025 was the warmest on record globally, more recent months of 2025 have experienced slightly lower but still very high temperatures, with July and August being the third-warmest for those months. Arctic warming continues to significantly exceed average temperatures, while European temperatures are rising faster than the global average, with the continent warming at more than twice the global rate since the 1980s. This means achieving colder than average months in winter is a lot harder than it was 20-30 years ago, given the warmer world.

Based on current forecasts for a central-tropical Pacific based La Nina cold anomalies, easterly QBO this winter and seasonal forecast it seems that, for this coming winter, we will see a slighter greater risk of northern blocking leading to cold spells - more likely in January and/or February - when there is an enhanced chance of a SSW occurring after New Year. However, overall at this early stage and given recent or current seasonal output, there is no signal for a colder-than-average winter (based on 1991-2020 average).

The expected developing La Nina impact on global circulations will not happen instantly given the inertia of the atmosphere and especially the oceans, particularly as it will be a weak and short-lived La Nina that may only last until next spring.

Also, despite the cooling of the central and eastern tropical Pacific, large areas of the northern Pacific are anomalously warm, some areas by a large margin. So, this larger scale warming over the North Pacific may mask the cooling affects of La Nina to something more akin of a neutral ENSO feedback on the atmosphere.

An increasingly unsettled end to autumn and start to winter, but greater chance for blocking with colder episodes in January and February interspersed with milder and unsettled weather.

After what’s looking increasingly likely to be a dry October, there is a signal for November to be more unsettled and perhaps December too, as the polar vortex becomes stronger and strengthens after a weak start in October, with a return of westerlies dominating much of the time. However in Jaunary and February, although westerlies will continue to dominate the weather at times, we think there is greater potential for high latitude blocking to occur, perhaps induced by a greater chance of a SSW at some point in the New Year.

Remember that these seasonal forecasts are not forecasts strictly speaking, they constitute a trend, based on the analysis of the predominant signals from certain weather models. At this time, factors may intervene and modify this trend, in particular the behaviour of La Nina: this will be the climatic parameter to follow carefully in the coming weeks, and which could lead to possible changes in the final winter forecast – which will be issued late November.

Loading recent activity...