A week ago, the medium and long-range forecast models were near-unanimously suggesting changeable west to south-westerlies for much of the first half of March, with high pressure to the south and south-east perhaps exerting a greater influence on our weather after midmonth. Since then, the outlook has changed completely for most of Britain, with the high pressure forecast for later in the month being pushed forward to the first week. High pressure looks set to stay over the south and south-east of Britain throughout this week.

There will, however, often be a north-south split in sunshine amounts, with cloudier weather frequently affecting most of Scotland and Northern Ireland, and at times penetrating into northern England. The most reliably sunny weather will be found in southern and eastern England, which will make a change from many recent months when the south-east has often been cloudier relative to normal than other parts of the country. North-west Scotland will be wet at times, but the rest of the country will generally remain dry.

A warm spell is forecast from late next week into the following weekend with winds turning southerly, although these southerly winds next weekend could bring rather more cloud for most of us. By next Friday, we may well see temperatures widely reaching around 15C over much of England.

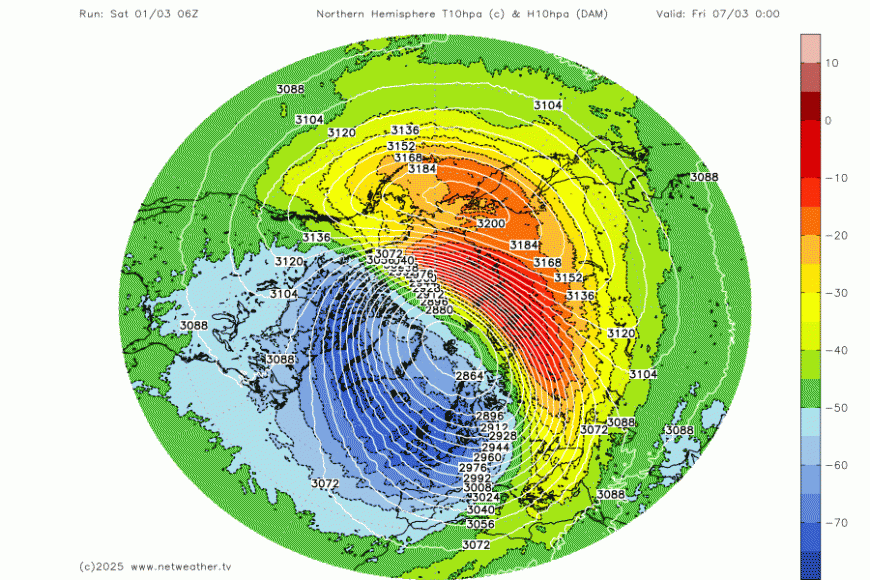

The ECMWF 42-day outlook has high pressure and southerly and south-westerly winds being dominant for a large part of March. However, a potential "spanner in the works" is the likelihood of a sudden stratospheric warming event during the first half of March. This tends to result in the break-up of the polar vortex (low heights over much of the Arctic), an increase in blocking highs over the Arctic, and an increased likelihood of cold air outbreaks in the Northern Hemisphere.

It doesn't necessarily guarantee colder weather for Britain, because if a blocking high sets up to the east and south-east of Britain, it can pull in very warm air masses, as happened in February 2019 following a sudden stratospheric warming in January 2019. For most of the country, high daytime temperatures were accompanied by bright sunshine, and on the 26th, the highest temperature was 21.2C at Kew Gardens, London.

However, it does increase the likelihood of colder outbreaks affecting Britain. An extreme example was the sudden stratospheric warming event in February 2018, which was followed by two snowy easterly outbreaks. The first occurred on 28 February/1 March 2018, dubbed the "Beast from the East," which brought many snow showers on the 27th and 28th, accompanied by thunder in some eastern counties, especially around Newcastle, and then heavy persistent snow in the south on 1 March, triggering a rare red weather warning from the Met Office. A second easterly followed on 17/18 March 2018, which is easily overlooked because of how potent the earlier one was. Many areas had snow showers on the 17th, and then longer spells of snow affected a large part of southern England on the 18th. Parts of the West Country, which are normally relatively snow-free and see average maximum temperatures well over 10C in March, had persistent snow and daytime maximum temperatures within a degree of freezing.

2018 Beast From the East Seeing as this wasn't too long ago, there doesn't seem to be a historic weather thread for this event. The airmass was exceptionally cold. Just imagine if it arrived a month earlier! We could have had a spell that ran Jan 1987 close for depth of cold. Netweather Community Weather Forum

2018 Beast From the East Seeing as this wasn't too long ago, there doesn't seem to be a historic weather thread for this event. The airmass was exceptionally cold. Just imagine if it arrived a month earlier! We could have had a spell that ran Jan 1987 close for depth of cold. Netweather Community Weather Forum Many sudden stratospheric warming events generate outcomes somewhere in between, often on the cold side but not necessarily particularly snowy. Historically, March and early April has often been a time of year when snow is relatively common, although it has typically melted quickly when the sun comes out during the daytime. In recent decades, there has been some shortening of the snow season, and some weather patterns that used to bring snow in early spring have become more likely to deliver sleet or cold rain for most of us.

Already some of the medium-range forecast models are starting to show high pressure developing to the north of Britain and bringing in colder air, although there is considerable uncertainty over this, and there are no guarantees that high pressure won't stay close to southern and south-eastern Britain.

February 2025 felt cold for much of the month due to a prolonged cold cloudy easterly spell for most of us, but in reality, mean temperatures were not far below the long-term average during this spell. Although the days were much colder than average, this was partly offset by relatively warm nights under the cloud cover. A mild end to the month has more than compensated for this, and so much of the UK has ended up around 0.5 to 1C above the most recent 30-year mean (1991-2020) and around 1.5 to 2C above the old 1961-1990 average.

It has been another odd winter, when westerly winds were expected to blow frequently because we have moved into a La Nina event in the south Pacific, but in the event, prolonged spells of westerlies have been relatively short-lived and few and far between. However, it has still been a milder than average winter overall, with a cold January being outweighed by milder than average conditions in December and February.

Loading recent activity...