You may have noticed that it has been rather showery this past week or so and although Friday and the weekend should see fewer showers then recent days, they will likely be back on the menu for next week.

Showers can occur any time of year of course, but why do we seem to get several days in a row with showers in April?

There are several factors that contribute to April getting its notoriety for being showery. In April, the land starts to warm up as the sun gets higher in the sky and has longer to heat the ground. However, the seas surrounding the UK and Ireland take a lot longer to warm up after the winter, as water’s heat holding capacity means that the seas take longer to warm up than land, though also take longer to cool down after the summer. So when a cold polar or arctic-sourced airmass covers the UK after crossing a cold sea, the land heating up in the sun can cause big temperature contrasts between the surface and the mid-to-upper levels of the troposphere. This contrast in temperatures, or decrease of temperature with height, at different levels of the atmosphere is known as the Lapse Rate.

In early to mid-Spring, the arctic or polar regions to our north, northwest and northeast are still cold enough to bring bursts of air as cold as we see in winter to the UK in contrast to increasing warmth in the sun. This is often facilitated by the upper flow that often become more sluggish and convoluted in pattern, i.e. allows cold artic or polar air to spread south across the UK.

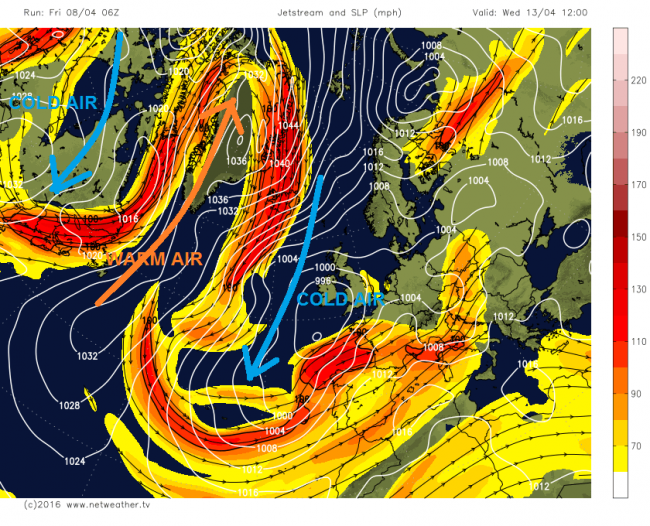

Convoluted or wavy jet stream, common this time of year, allows cold polar or arctic air to spread across the UK, bringing large temperatures contrasts between the surface and upper air.

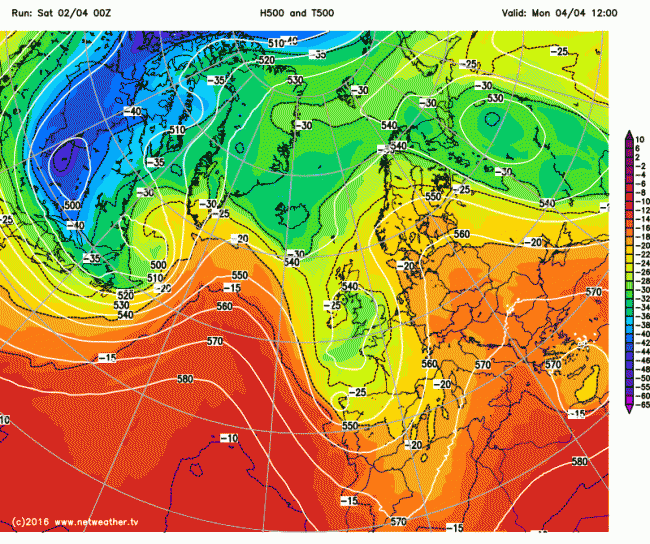

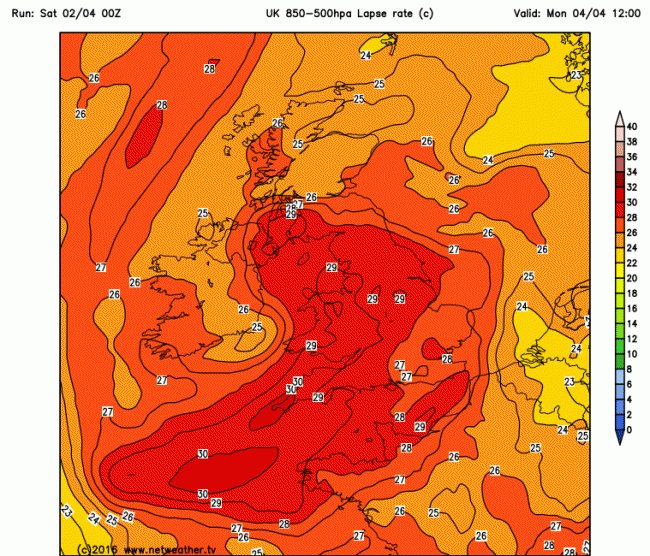

The two weather charts below from Monday this week will, I hope, illustrate how to spot these temperature contrasts. The 1st chart shows an upper cold pool or polar origin across the UK, with the temperature at 500mb (about 5000 metres up) below -25C. The temperature difference between 500mb and 850mb (about 1000m up) is 29-30C in some areas. This suggests strong instability at the cloud level. The temperature contrast between the surface and 500mb likely even steeper with surface heating during sunny spells. So rising parcels of air warmed at the surface are likely to gain enough height to form showers.

GFS 500mb temperatures and heights for 12z Monday 4th April 2016 shows cold pool over UK:

GFS 850-500mb lapse rates for 12z Monday 4th April 2016

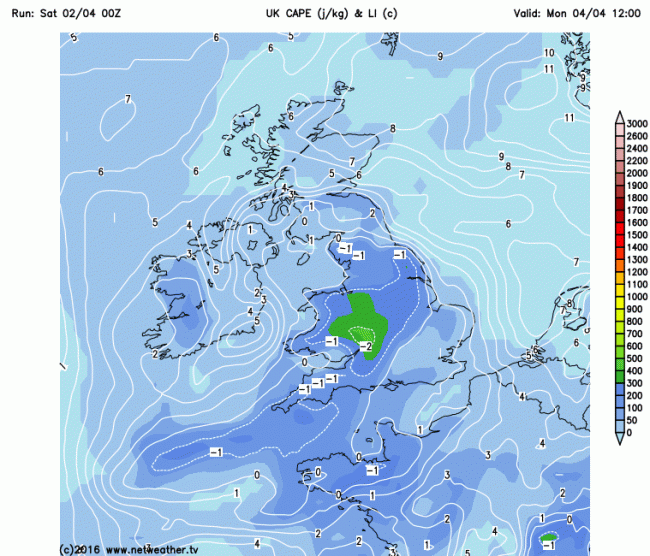

GFS CAPE (Convective Available Potential Energy) and Lifted Index chart for 12z Monday 4th shows amount of convective energy available - generally a few 100 j/kg CAPE and LI of 0 or below is sufficient for hail and thunder - the higher the CAPE the more severe a storm.

The combination of cold temperatures aloft and low pressure in the atmosphere allows parcels of air warmed just above the ground, created by the sun to rise. The larger the difference in temperature between the ground and higher up in the atmosphere, the more unstable the air becomes and the more readily parcels of air will rise. These parcels of warm air will continue to rise if the air surrounding the rising parcel is always colder. These rising parcels of air eventually cool and expand, and as cool air can’t hold as much water vapour as warm air, the water vapour condenses into clouds.

However, as condensation is a warming process, it keeps the air inside the cloud warmer than air surrounding it. This keeps the air unstable and allows the cloud to keep growing upwards to great heights into what are known as cumulonimbus clouds. These clouds build to heights that are well below freezing, so super-cooled water droplets in the cloud collide and eventually form hailstones which become heavy enough that they can no longer be supported by the updrafts in the cloud and thus fall to the ground. Eventually, the cumulonimbus cloud grows so high it reaches a stable part of the atmosphere, often the top of the troposphere / bottom of the stratosphere, where the top of the cloud spreads out into the characteristic ‘anvil’ – this tends to be when lightning and hail are produced by the cumulonimbus cloud.

Hail in April Showers is quite common, as the freezing level of the air tends to be a lot lower than in the summer or autumn, so the hailstone has less chance to melt before it hits the ground. Though generally hailstones tend not to get as large as in the summer, because generally the cumulonimbus clouds do not get as high given less heat at the surface.

April showers often provide some great cloudscapes too, as the showers are often interspersed by areas of blue sky. And the unstable polar airmass that enables these showers also bring very good visibility too, so the bright while cauliflower cumulonimbus clouds stand out well against the blue skies. So although the showers can catch us out, they can also be a marvel to see before they arrive or once they pass.

Loading recent activity...