The Met Office published a few days ago that April the sunniest on record and the third warmest. It was also another dry month, following a dry March, with parts of the Midlands and NE England seeing less than a fifth of the average April rainfall.

March and April have both seen persistent blocking high pressure bring settled conditions during most of both months and May is following suit so far.

00z ECMWF ensemble mean indicates high pressure dominating UK weather through to mid-month at least:

The dry conditions have prevailed into the start of May and there are currently no signs of any rain for most over the next few weeks either. The dry conditions combined with warmer than average temperatures have contributed to a higher-than-usual number of wildfires for the time of year in many parts of the UK, raising fears for wildlife and vegetation. Farmers are also concerned about the effects of the dry weather on their crops, particularly at this stage of the growing season.

This contrasts with 2024 – a year that was very wet in certain areas, especially central and southern England. The Thames and Severn Trent regions registered their third and fifth wettest years, respectively

Very dry spring so far - rainfall anomalies below show large deficits across many parts - data from Starling Roost Weather

This swing from too wet to last year to too dry so far this year means that farmers are struggling with increasingly unpredictable weather. It was too wet across much of England in the autumn – which prevented many farmers from drilling their crops, to far too dry now, with crops showing signs of stress as a result of low rainfall. Last year’s harvest was one of the worst on record after 18 months of relentless rain, this year’s crop could also be a disaster if there’s no rainfall in the next few weeks.

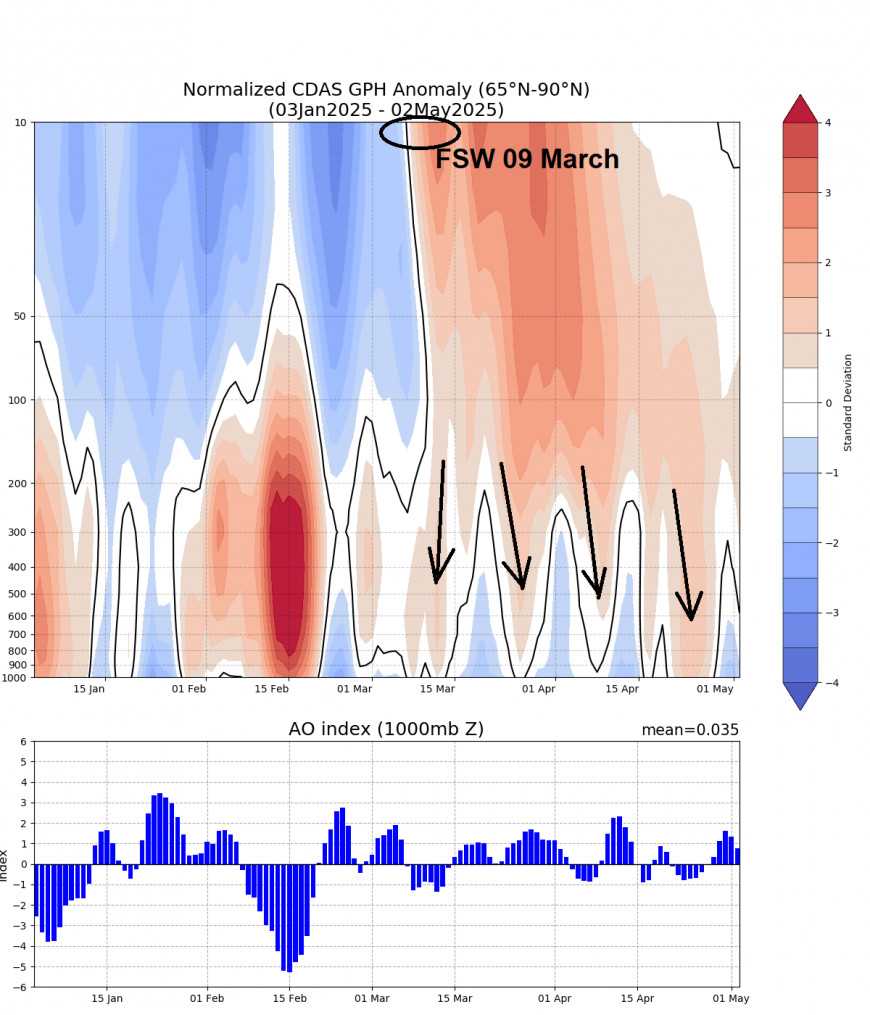

The unusually early Final Stratospheric Warming, the second-earliest final warming since 1958, is likely one of the main culprits behind the unusually persistent blocking pattern that has prevailed across northern Europe, diverting the normal storm Atlantic storm track way to the north and south. Southern Europe, more especially Spain & Portugal has seen a very wet spring so far.

The final stratospheric warming or reversal of winds from westerly to easterly in the polar upper stratosphere at 10 hPa at 60N occurred on the 9th March. A final stratospheric warming occurs when the reversal to easterlies never experience enough polar night cooling to return to westerlies but remain easterlies throughout the summer season.

Last year, a sudden warming occurred on March 4th, but the vortex then recovered, and the final warming didn’t occur until April 28th. But this year, the has not recovered and will not return over the North Pole again until late autumn.

About three weeks after the final stratospheric warming in early March, stratosphere-troposphere coupling occurred, with reversal of westerly winds reaching propagating down from the upper stratosphere reaching the troposphere. This was signalled by an increase in air thickness evident throughout the stratosphere and troposphere over the pole – which is also linked to higher pressures and warmer than normal temperatures over the polar region. When this coupling occurs with reversal of winds propagating down to the troposphere, the resulting disruptions in the jet stream can increase the odds of blocking high pressure systems developing and persisting at higher latitudes – such as over northern Europe, as we have seen since early Spring.

However, the effects of the final stratospheric warming (FSW) can often persist for a while, like this spring, with the reversal slowly ‘dripping’ down into the troposphere during April and perhaps through much of May too. This allows blocking over northern Europe to persist over a long period.

The FSW may not be the only driver of the persistent blocking that’s brought prolonged dry and settled weather, but could be one of the main culprits.

Loading recent activity...