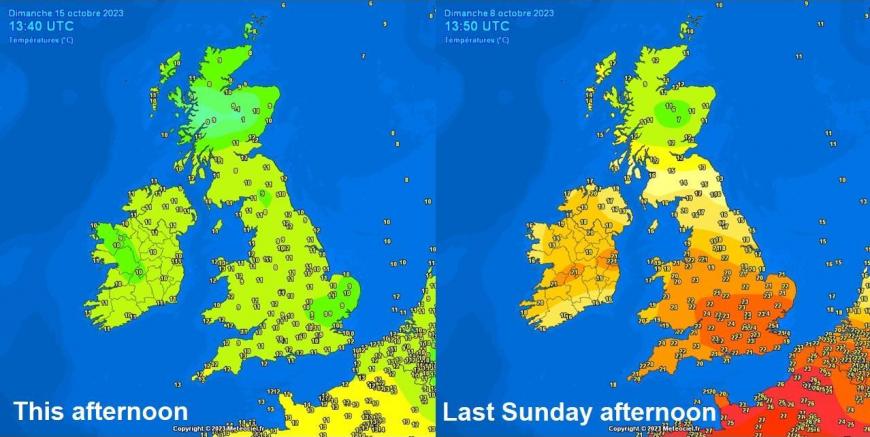

Finally, after weeks of well-above average temperatures, especially in the south where it’s been unseasonably warm since August, for all parts of the UK started to feel more like autumn this over the weekend, with cool days and cold nights, there’s even a touch of ground frost in the south. The autumnal chill is just normal though, nothing out the ordinary, unlike the recent warmth. Last weekend saw 25C+ reached both days in the south and Monday saw 26.1C in Kent, the warmest of the recent spell. Today the same places that saw mid-20s are reaching 10-11C at best on Sunday 15th.

But we may have seen the back of temperatures reaching the mid-20s until next year and with some autumnal chill this weekend giving us a reminder that winter is just round the corner. But what are the current signals for how the coming winter may pan out?

There are a number of models that produce seasonal outlooks, ECMWF, UK Met Office and GFS are the main ones to look at and they have updated with their October outlooks recently, so we firstly we will look at those and also at the cross-model blend to see if there’s any consensus.

But there are also a number of drivers to look at that can typically work in tandem or against each other through the winter period that we have already clues to how they may influence weather patterns during the season.

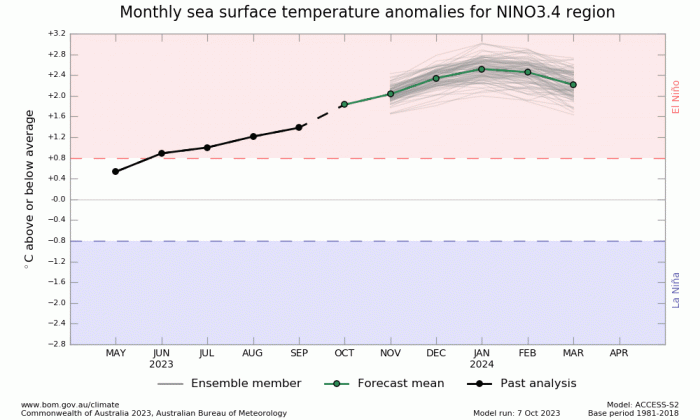

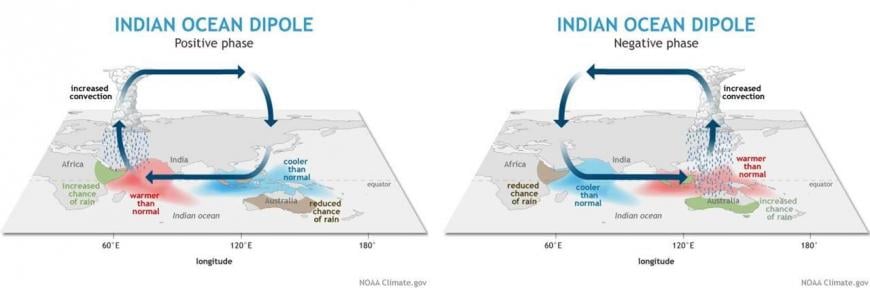

One of the most influential drivers is the El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO), the warming or cooling of the central and eastern tropical Pacific, which is one of the most important climate phenomena on Earth due to its ability to change the global atmospheric circulation, which in turn, influences temperature and precipitation across the globe. There is also the influence of Indian Ocean Dipole, another prominent mode of air-sea interaction which can affect weather patterns in the mid-latitudes.

There is also the Quasi-Biennial Oscillation (QBO) – which is a changing wind anomaly in the tropical Stratosphere. Its presence has been well known for many decades, and it appears to play a crucial role in the seasonal weather patterns at higher latitudes, including the Polar Vortex. Also, the Hunga Tonga volcanic eruption early last year released huge amounts of water vapour into the tropical stratosphere which has now spread globally at that high level of the atmopshere to reach the northern and southern polar regions. There is suggestions that this extra water may cool the polar stratosphere and thus strengthen the polar vortex this winter.

Finally, there are more local ocean interactions, i.e. North Atlantic Sea Surface Temepratures (SSTs) that may affect temperature and even the position of the jet stream.

ECMWF Mean 500 hPa heights for DJF

ECMWF Mean T2m for DJF

The ECMWF October update is quite a change from previous few updates. Gone is the negative North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) on previous updates – with high latitude blocking and southerly tracking jet/troughing to the south, which could bring cold and wintry episodes to USA and Europe. In comes a +NAO with stronger polar vortex / troughing at high latitudes and high pressure to the south – bringing a milder outlook for the winter. Then for February, EC has mean trough over the UK.

Other models:

GFS Mean 500 hPa heights for DJF

GFS Mean T2m for DJF

UKMet Mean 500 hPa heights for DJF

UKMet Mean T2m for DJF

C3S Mean 500 hPa heights for DJF

C3S Mean T2m for DJF

Conclusion: a mixed picture from the big three players, ECMWF, GFS and UKMO. All models for December, including the C3S multi-model outlook, indicate a trough signal to the west. This would mean mild and perhaps unsettled at times. Models then diverge for January – EC has a mean trough to the west, GFS a mean trough to the north, UKMO has mean ridge to north and trough to the south, C3S multi-model has trough over NW Europe and ridge to north. For February, EC has mean trough over UK, GFS and UKMO has mean trough to the north/northeast, ridge to the southwest. C3S has trough signal to the west.

ENSO (El Nino Southern Oscillation)

ENSO has three states, or phases either: “El Niño” – which is above-average sea surface temperatures (SST) in the central and eastern tropical Pacific; the opposite “La Niña: which is below-average sea surface temperatures (SST) in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean; or Neutral: tropical Pacific SSTs are generally close to average.

.png?w=870)

An El Nino is currently underway, which was declared back in July and looks to strengthen as we head towards winter. I could produce composites of winter months that had a year with a developing El Nino prior, but there are other drivers at play too that can work in tandem or against the typical El Nino forcing on global patterns - which will be discussed further on.

El Niño years have a tendency to have a mild wet and westerly start to winter (Nov-Dec) and a colder, drier end to winter (Jan-Mar) across most of northern Europe, on average.

However, El Nino is competing with marine heatwaves in other regions of the globe since it developed in July – such as the North Atlantic and also the northwest Pacific near Japan. So, the combination of multiple areas of forcing on the atmosphere from warm SSTs areas could yield new patterns not seen before and which could make analogs of El Nino redundant, especially years pre-2010.

North Atlantic SSTs

The North Atlantic remains anomalously warm across much of the basin, particularly west of mainland Europe and southwest of the British Isles. This pool of warmth could keep temperatures above average should the flow come from the west or southwest in the first half of the winter at least. But also moderate the cold air in polar flows from the west or northwest.

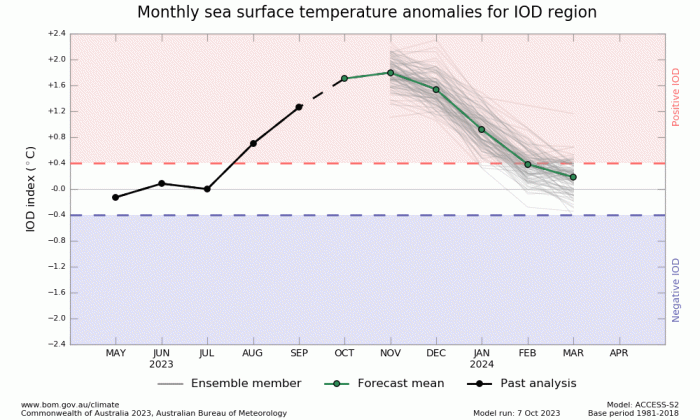

IOD

The Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) is a prominent mode of air-sea interaction in the tropical Indian Ocean. During a positive IOD event, the sea surface temperature (SST) is anomalously cool in the southeastern Indian Ocean and anomalously warm in the western Indian Ocean, accompanied by pronounced anomalous easterlies over the central equatorial Indian Ocean and anomalous southeasterly along the coast of Sumatra. Negative IOD events are the opposite, with cool SSTs in the west and warmer-than-normal SSTs in the east.

The impacts of the IOD are not only felt in the tropics, but can also influence weather patterns across much of the mid-latitudes. The phase of the IOD contributes to determining important aspects of local and global climates.

A positive IOD is currently continuing to strengthen. The IOD index is +1.85 °C for the week ending 8 October. This is the sixth-highest weekly IOD index value since records began in 2001, with all higher index values observed during the positive IOD of 2019. All models predict this positive IOD is likely to continue into at least December. Northern Europe and the UK experienced an exceptionally warm and wet winter in 2019/20, driven by an anomalously positive North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO). Analysis and model experiments show that the +IOD was a key driver of the observed positive NAO that winter. The model experiments found 2 teleconnection pathways of the IOD to the north Atlantic emerge: a tropospheric teleconnection pathway via a Rossby wave train travelling from the Indian Ocean over the Pacific and Atlantic, and a stratospheric teleconnection pathway via the Aleutian region and the stratospheric polar vortex.

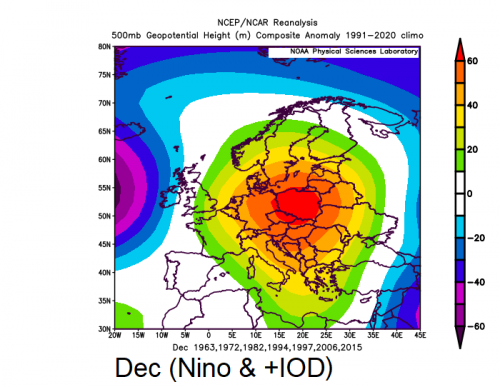

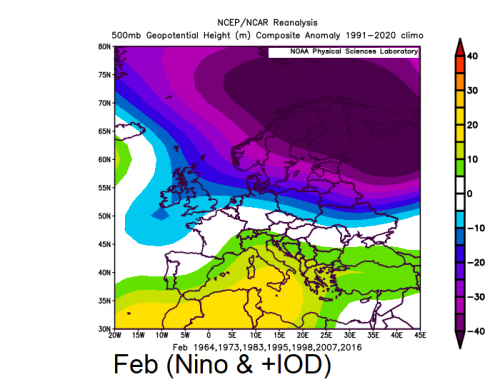

El Nino and IOD combo

Some positive IOD events, but not all, occur at the same time as an El Niño, but the relationship between El Niño and the IOD is complicated. There have been 7 positive IOD events that coincided with El Niño since 1960. These years were: 1963, 1972, 1982, 1994, 1997, 2006, 2015. This is the European 500 hPa height mean for each winter month.

.png?w=500)

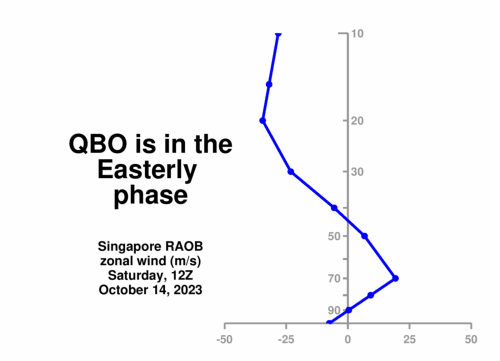

QBO

The QBO is a tropical, lower stratospheric, downward propagating zonal wind variation, with an average period of around 28 months. The QBO affects climate phenomena outside the tropical stratosphere, including ozone transport, the North Atlantic Oscillation and the Madden–Julian Oscillation.

The QBO is currently in its east (negative) phase and will continue easterly through the winter. This indicates the potential for a weaker jet stream, greater chance of sudden stratospheric warming events, and increased chance of cold wintry episodes across the parts of the US, Canada, and parts of Europe.

During an easterly QBO, the Polar Vortex and stratospheric winter circulation tend to be weaker, leading to an increased likelihood of Sudden Stratospheric Warming (SSW) events. The combination of El Niño and an east QBO increases the odds for a Polar Vortex collapse and an SSW leading to an increased chance disruptions in the jet stream and a release of colder Arctic air into Europe and the US.

Hunga Tonga Eruption in February 2022

The huge amount of water injected by the cataclysmic Hunga Tonga volcanic eruption into Earth's atmosphere last year has now reached the stratosphere over the North and South Polar regions. It is thought to be responsible for creating an ozone hole recently in the southern polar stratosphere. But also the amount of water in the stratosphere has increased by 10% since the eruption – with this water vapour having spread from the equator to the poles. This injection of water vapour into the northern polar stratosphere may lead to stronger cooling and thus a stronger polar vortex this winter. So this could perhaps cancel out or compete against the historical signal for El Nino and easterly QBO to bring more northern blocking, southerly tracking jet and increased risk of cold spells to northern Europe.

There are other drivers too, but most of these cannot really be looked at until nearer winter to get a handle on how they may influence weather patterns.

Although some models' seasonal outlooks on their October update, ECMWF in particular, have abandoned their earlier signal for high latitude blocking and southerly tracking jet through much of winter, there is some signal for such a scenario at the back end of winter – which ties in with the El Nino / eQBO analogs that suggest mild Dec and also Jan then backloaded chance for colder weather later in winter. Warm Atlantic SSTs and also the positive IOD and El Nino combo call for mild winter patterns to prevail, too, if the IOD is as strong as 2019, then this could mean a mild winter. So all-in-all, no strong signal for a colder-than-average winter, but a stronger signal for milder-than-average. The greatest chance for colder spells later in winter.

In conclusion of the above, I’m strongly swayed to thinking that December and perhaps a good chunk, if not all of January, will be mild and sometimes, if not much of the time, unsettled. Upper trough likely close to the west or extending over the UK, and high pressure over SW Europe much of December and 1st half of January, so winds from the southwest or west, rainfall above average. A small chance that troughing may relax to allow pressure to build over Scandinavia and extend west, bringing colder / settled weather briefly. The second half of January or early February onwards may see greater potential for northern blocking episodes but with blocking highs more likely to form to the west or northwest over Greenland and potential for cold northerly winds occasionally but also Atlantic systems crossing the UK on a more southerly track.

It’s very early days, and signals may change over the rest of autumn before my full winter forecast is issued in late November.

Loading recent activity...