There are increasing stirrings on the media airwaves over the last few days of a potential Sudden Stratospheric Warming (SSW) in the next few weeks, even suggesting that one is likely and to be on alert for a potential ‘Beast from the East’.

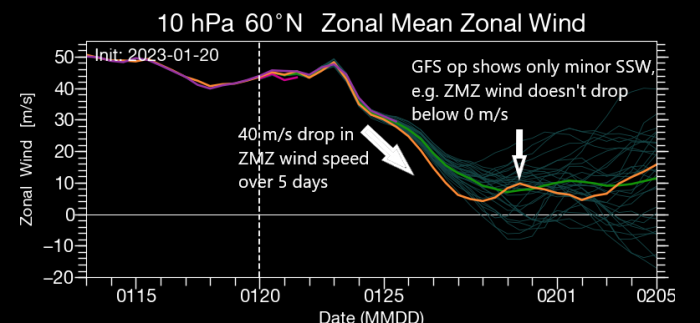

In reality, most weather models that forecast the stratosphere are on board with at least a minor SSW, with a deceleration of zonal winds from 45 m/s on the 23rd to around 10 m/s on the 27th. But as of yet, only a fraction of ensemble members of the most recent model runs are going for a major SSW, i.e. 10 hPa zonal (westerly) winds at 60N reaching 0 m/s then reversing.

To understand a SSW and its implications to our weather, we first need to understand the stratospheric Polar Vortex. The polar vortex is a strong band of westerly winds in the stratosphere, known as the polar night jet, surrounding the North Pole 10-30 miles above the surface that appears in autumn and is, on average, at its strongest in January, before weakening in April. The polar vortex is absent after then and through the summer, with winds easterly in the polar stratosphere. When the polar vortex is strong the jet stream in the troposphere, where our weather happens, tends to be stronger and shifted towards the pole. This means cold air tends to be locked up over the arctic.

Source: Simon Lee / simonleewx.com - The February 2018 major SSW, the split of the polar vortex at 10 hPa which eventually lead to the Beast from the East later in the month.

Cross section of atmosphere shows wind reversal to easterly (blues) high up in the stratosphere (major SSW) in early to mid-February 2018 which eventually propagated downwards to the troposphere, triggering the late February 2018 Beast from the East.

Large waves in the jet stream in the troposphere, known as Rossby waves, can propagate upwards into the stratosphere. There are 1 to 3 of these large waves that can occur at any one time and when they break in the stratosphere they can decelerate the polar night jet. This weakens the polar vortex and can reverse the winds from westerly to easterly – causing a warming in the stratosphere as the air in the stratosphere collapses and compresses. The term SSW refers to a rapid warming (up to about 50 °C in just a couple of days) in the polar stratosphere.

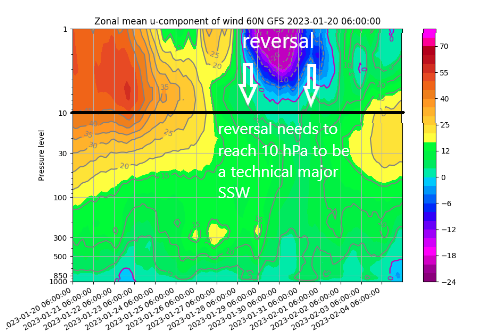

The temperature and wind anomalies associated with a SSW can descend down into the troposphere, bringing significant impacts to northern hemisphere surface weather patterns. Typically, this can eventually manifest in the tropospheric jet stream weakening, which allows cold air bottled up near the polar cap to escape and cause cold air outbreaks over much of Europe, parts of Asia, and the USA. The downward propagation of the reversal of zonal winds and warming in the stratosphere into the troposphere can take weeks or even months and impacts at the surface are not guaranteed and they are not necessarily experienced everywhere.

Every SSW is different and around 66% of them lead to colder conditions, so not all SSW events lead to cold. For example, the SSW in February 2018 led to the ‘beast from the east’ later that month and into early March, whereas the SSW in January 2019 had no significant impact for the UK and NW Europe, due to the easterly winds in the stratosphere not propagating down into the troposphere. In fact, it stayed mild for the rest of the winter.

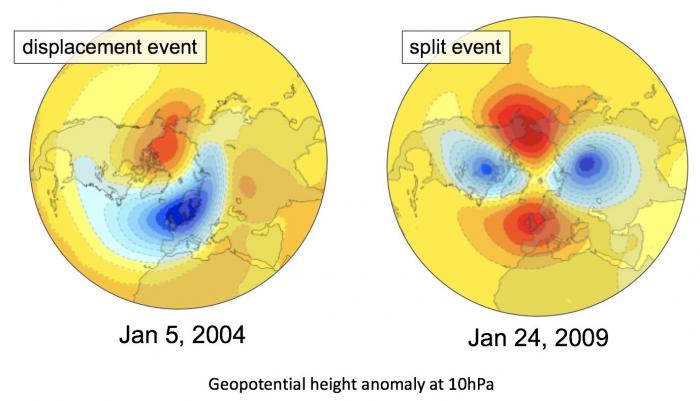

An SSW can be either major or minor. Major SSWs occur when the winter polar stratospheric westerlies reverse to easterlies and they often lead to a split of the polar vortex into two separate vortices that displace away from the pole, one usually moves over Eurasia, the other over North America. In minor warmings, the polar temperature gradient reverses but the circulation does not, this can lead to displacement of the polar vortex away from the pole towards Europe, N America or Asia. The type of SSW, be it a displacement or split event, is important for the tropospheric response.

The tropospheric weather patterns that typically occur prior to an SSW split event are a persistent low pressure weather system over the North Pacific, known at the Aleutian Low and a high pressure weather system over the North Atlantic and Eurasia and this pattern has been evident in recent weeks leading the forecast for the stratosphere to warm by the end of the month. The split is usually forced by 2 Rossby Waves, which consist of wave-1 and wave-2. Wave-1 typically being from the North Pacific towards the pole, wave-2 from North Atlantic / Eurasia. An SSW displacement is typically caused by just wave-1 forcing.

There can be a lot of variability from one SSW event to another in terms of who may get hit with the extreme cold and snow that are often associated with these polar vortex events. The location of cold air outbreaks may depend on where the polar vortex splits or displaces, as well as what other factors, like ENSO, are influencing the weather at the time.

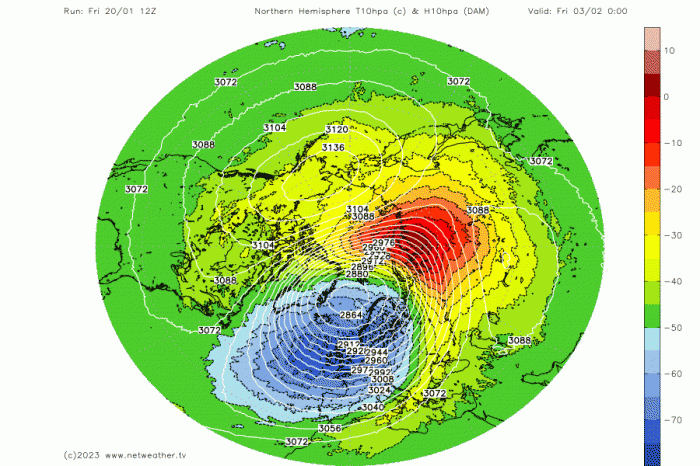

A minor SSW, which is looking likely, is generally less likely to impact surface weather patterns than a major SSW. A minor SSW will likely cause a displacement of the stratospheric Polar Vortex over the next couple of weeks. The polar vortex is modelled to be displaced towards northern Europe.

12z GFS shows the polar vortex displaced from the pole towards northern Europe by early February

A major SSW can still occur after one or two minor warmings that weaken the polar vortex prior, and there is some support from ensembles for this occur. Though most recent model runs suggest only 20-30% chance of a major SSW with zonal mean zonal winds at 10 hPa 60N reaching 0 m/s.

So, in a nutshell, there looks to be a minor SSW by February, but this only looks to displace the polar vortex away from the pole. The displacement may not change much at the surface though, with the background La Nina and MJO moving over the Indian Ocean more likely continuing to force the pattern – which typically means +NAO in early February with a return of mobile Atlantic westerlies bringing unsettled and milder conditions. The caveat is that recent weather patterns this winter have not necessarily conformed to the typical imprint of La Nina forcing, so there is still uncertainty how the upcoming more blocked weather patterns will evolve as we head into February. If a major SSW does occur, which there is no concrete evidence of occurring for now, then this could change things and override other drivers such as La Nina and MJO. But if one does occur, it could take several weeks for impacts to be noticed at the surface. Which could mean late February or even into March.

So it’s probably best to ignore any stories that suggest a SSW is going to lead to the Beast from the East such as occurred in late February and early March of 2018.

Loading recent activity...